Female artist photography science

With the help of Ms. Felice Frankel, the scientists turned dull images of things like yeast on a plate or the surface of a CD, into impressive images. "She changed the visual face of science," said Dr. George M. Whitesides, a chemist at Harvard University.

Art is not a visible concept

When called an artist, Felice Frankel often frowned. First of all because the pictures she took were not for sale. After receiving a grant from the Guggenheim Museum in 1995, she began bringing her work to the gallery, but no one was sad to see it. Second, her photographs do not include emotions, ideology or any other message.

She said: "My material is the natural phenomena such as the magnetic field, the activity of water molecules, or the growth of bacteria. I don't call it art. Because if it were art, it has to say more about the creator of that work, not just the concepts seen in images. "

Ms. Felice Frankel in her office working at MIT (Image: Nytimes)

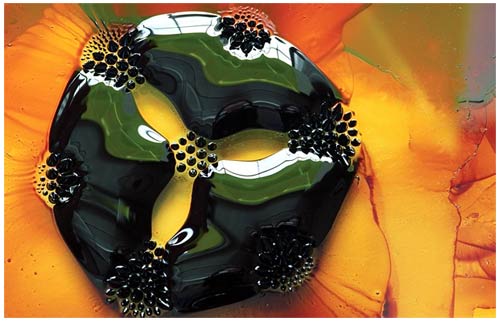

As an artist, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and currently a senior research fellow at the Computational Innovation Institute at Harvard University, she helps researchers. Use cameras, microscopes and some other instruments to show the beauty of science. One of her photographs, the vivid image of an iron-rich fluid under the influence of magnets, was so widespread that she became "fed up with it".

To get that picture, she did a very common gesture. She slid back and forth on a yellow note pad under the glass laboratory where the liquid was placed. That movement did not change the experimental conditions, but it captured the image of the liquid in such a focused way that the National Science Foundation made a promotional poster. Report with that photo.

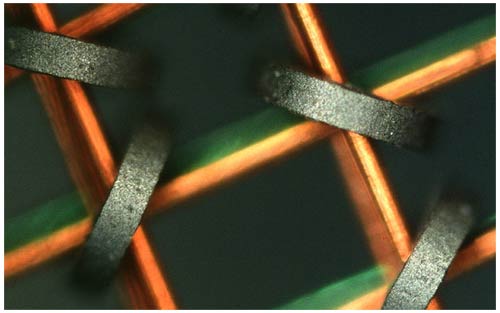

A nucleus of a computer memory chip (memory chip) taken through a microscope (Image: Nytimes)

Science photos must be attractive for art

Ms. Frankel is holding conferences across the United States with the theme of Image and Meaning, and is promoting to establish a program funded by the National Science Foundation on the use of visual images in teaching. science. With her colleague, she is setting up an online website where researchers can talk about the concepts they want to convey in the images. But she didn't think her pictures had to explain everything. "For me, it is important to attract people to view scientific photographs, even if they do not know it is science," she said.

To achieve this goal, she sometimes edited the images. For example, when she took a picture of bacteria growing on agar, it could be seen that the agar was cracked, but she wanted the reader to pay attention only to the bacterial shapes, so she digitally erased it cracks. Another time, she photographed a stick-shaped orange bacterium, and the camera couldn't reproduce the orange she could see through a microscope, so she added that color.

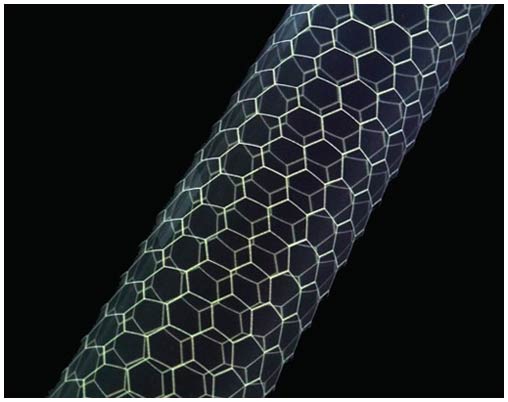

Snapshot illustrating the structure of a carbon nanotube tube (Image: Nytimes)

"This trick is acceptable, because their purpose is not to hide or distort scientific information, but to make it clearer," she said. And when such images appear in scientific journals, an unmodified original copy will be posted online with additional details.

Frankel always tells readers what she did when creating a photo. She also discussed with her colleagues how to do it. "If editing the photos to make them look better is acceptable, provided that the tricks are done," she said.

That's the way magazines like Scientific American do when they use her work - they inform readers that the image in question has been changed, and how it changes.

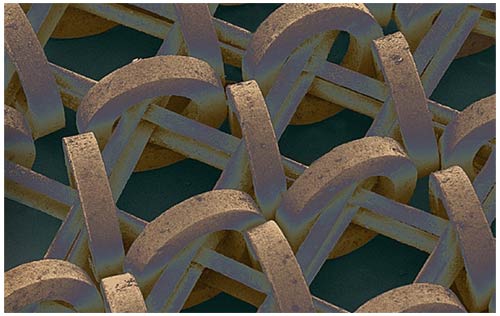

Plastic printed sheets of electronic circuits (Photo: Nytimes)

"Science is always in my soul"

For 62-year-old Frankel, this job is a return to a great passion for her youth. Born in Felice Oringel, Brooklyn, she studied at Midwood High School and the University of Brooklyn, where she majored in biology. After graduating from college, she worked at a cancer research laboratory in Columbia.

But life did not go the way she wanted. She is married to Kenneth Frankel. He was taken to Vietnam. When he returned, they moved to Massachusetts, where he worked as a breast surgeon and they had two sons. When Mr. Frankel returned from Vietnam, he brought a gift with him. It was a very good camera. And she started taking pictures.

The fermenting agent (yeast) accumulates in a laboratory dish (Image: Nytimes)

The beautiful photos inspired her to continue taking them. She was originally a volunteer photographer for a television station, then an architect. Soon she began landscape photography for the magazine and for a book on modern landscape architecture. She then traveled throughout the United States to take photos of the landscape. Then she realized she was going the wrong way. She applied for a Loeb Scholarship at Harvard Design School, where she spent two years in 1991 and 1992 to finish her undergraduate degree. "I live in the science center, because I really want to go back to science," she said.

One day, someone introduced her to a course on molecular biology, and the professor presented the lecture visually. She introduced herself and was invited by the professor to his lab. That professor is Dr. Whitesides. "We started talking about the scientific presentation on the chalkboard," he recalls, "and at some point she commented that we did very badly, and I told her to show us. how to do it better ".

A computer memory chip taken through an electron microscope, then colored by digital (Image: Nytimes)

One of the first photos she took in his lab, small droplets of water were placed in rows on a laboratory glass plate with a waterproof mesh, printed on the cover of Science magazine. . "Since then, her influence on scientific media has been enormous," said Dr. Whitesides. "In addition," he added, "she has a very good sense of design and color. It is hard to say that she is not an artist." And Frankel said: "Science has always been in my soul."

"My material is the natural phenomena such as the magnetic field, the activity of water molecules, or the growth of bacterial particles. I don't call it art. Because if it were art, it has to say more about the creator of the work, not just the concepts seen in the images "

Iron-rich fluid under the influence of magnets (Image: Nytimes)

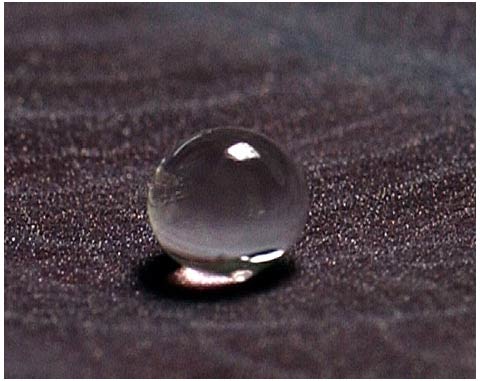

A drop of water (Image: Nytimes)

FIDITOUR TRAVEL COMMUNICATION COMPANY

Representative: Mr. Tran Van Long - Chairman and General Director

Head office: 95B-97-99 Tran Hung Dao, District 1, City. Ho Chi Minh.

Hanoi Branch: 66 Tran Hung Dao, Hoan Kiem District, Hanoi

Phone: 028 730 56789 | Hotline: 19001177